Neri&Hu’s new project in Yangzhou, a small city in China’s Jiangsu Province, opened in October last year, but Ms. Hu hesitates to call the resort brand new. “It’s a new construction in a place with an ancient history. Our job is to design a hotel that takes on some part of that history in this sort of district government-sanctioned project.

“And if you know about Neri&Hu,” she says with emphasis, “we like to take history as some way of thinking about design – particularly new design – and how to merge the old and the new, the past and the future.”

Every project for us is different; each one has its own specificity, Ms. Hu continues. “We like to dig deeper and hopefully find something in that project brief or that project site or that project program that we can hold on to and create a concept (around which) we can develop. That’s kind of methodology that we have as designer.”

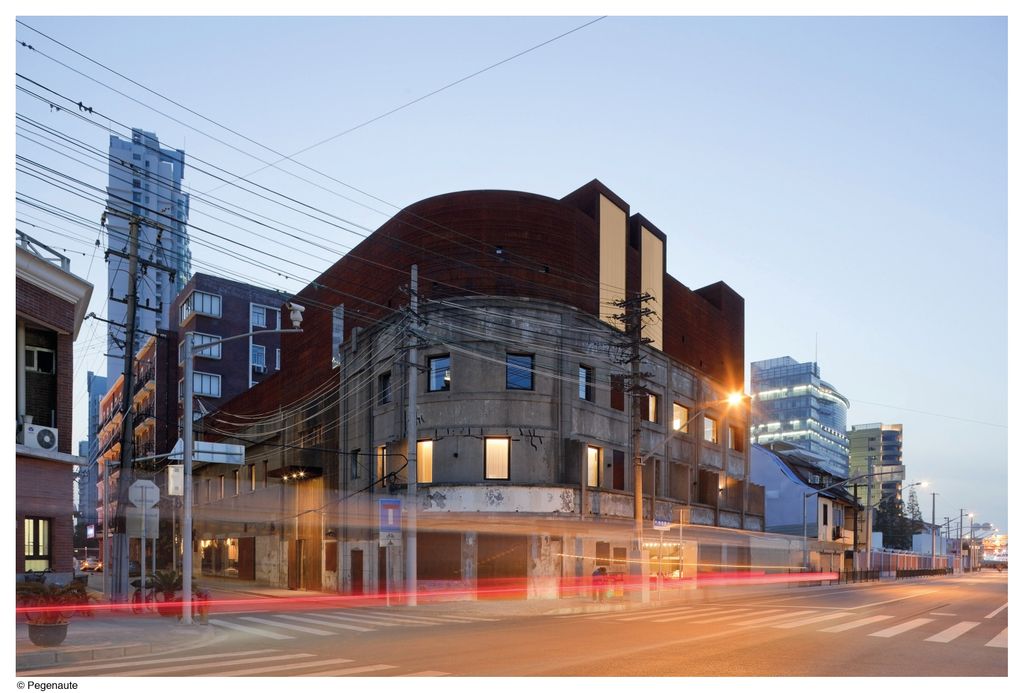

For the Yangzhou project, the history took the designers by surprise – not only was it rich, but that it had a kind of planning. “If you look at the old town, there are these old walls, which we took and recreated. (In the Waterhouse, another well-known Neri&Hu project, they used what was given to them as history before adding on to it until it became the project.)

“In this project we ‘created’ the history. It was kind of fun. We recycled these old bricks to create the grid of a village, and then we created the hotel on top of that grid.

“The reason behind that ceremonial passage is that we thought if you moved (a certain) way, you will get some insight into history that you would not if you were allowed to move freely.”

Ms. Hu thinks that Chinese urban planning, especially the ancient Imperial planning, whether one finds it in Beijing or Xi’an, always features some form of ceremony. “It’s also a kind of questioning contemporary society (about) the loss of that past, that liturgy. We thought it would be interesting to bring it back through a hotel project.”

“We’re always looking for a different kind of experience. Hopefully, it’s not like going home, or being in a hotel in a different city. We’re always looking for something very local that we can develop as a spatial subject, an architectural subject to play on. The movement then becomes part of the design.

If you look at what design is, and the way that a designer prepares himself for the work of design, you will find that it derives from who the designer is – his being, his humanity, Ms. Hu explains. “It’s difficult to presume another persona stepping into other people’s shoes because in some ways we have to be true to ourselves as designers.

“It’s almost like a musician or an artist, if you took on someone else’s hands or someone else’s tone, I feel that you are no longer designing as a designer.

“You can still be designing for other people, and we often do that when we design or work under somebody.” (Ms. Hu and her partner Mr. Lyndon Neri both worked at Michael Graves Architecture and Design, where the entire office had to design like the Post-Modern master, she says.) “So we had to take on his design philosophy and step into his shoes when we were designing a project.

“But when we’re designing as ourselves, we take on our own philosophy of life, we take on our history, our culture, everything.”

Ms. Hu acknowledges the fundamental differences between the design cultures of the East and the West. “As an Asian, we carry thousands of years of history, this flesh and blood – whether you’re Chinese, Japanese or Thai. And all that kind of binds us. I think, particularly, for Asians who have a long history in their blood, in their culture, we all feel that there’s a kind of burden, a cultural baggage, and it can be heavy sometimes.”

If one were a German person who went to live in the US, that lineage, somehow with immigration, with moving around, becomes diluted, and he is unburdened of that kind of heaviness, Ms. Hu elaborates. “That is one (difference),” she says, the other being a vastly different life philosophy. “For example, the way we look at history: The Western Greco-Roman history is a linear movement where there’s a beginning and an end; the Christian belief (enshrined in) the Alpha and the Omega is also definitely linear.” Ms. Hu surmises that Eastern philosophy derives from a cyclical worldview. “That is a totally different way of looking at the world, and the way we look at the world influences the way we design.”

These are the stuff of everyday conversations at Neri&Hu, Ms Hu shares. “We talk about this ‘sense of loss’ everyday. It’s a loss that all of us can relate to. Even before globalization, we’ve been experiencing losses: of time, of youth, of the past. And as we evolve, we lose many other things.”

If one were to look at the theoretical, discursive discussion about design, particularly about architecture, he will find two branches, Ms. Hu surmises. “There’s the new kind of regionalism that makes people want to hold on to history (in order to) recreate local culture and flavor. And then there is the classic modernist who feels that because of technology, we have to lose history and build on a tabula rasa – where you destroy everything and build anew. For us what is important is to find a balance.

“That balance is difficult to find and I think that’s one of the reasons why Neri&Hu is always given these projects where we have to work with history. The way that we find balance is by somehow bringing back history and introducing them in new projects.

Back

Back