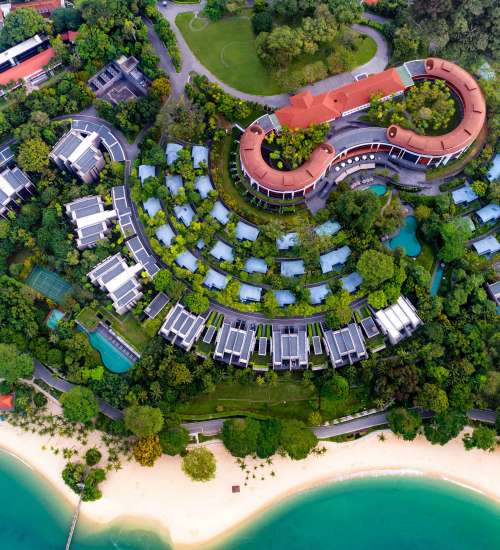

In 2011, when Italian architect Mr. Roberto Baciocchi first visited Rong Zhai, a Western-style mansion in Shanghai, he found the property in a state of neglect. “Many parts had been damaged,” he recalls. “But fortunately no very aggressive alterations had been made.” Located behind a leafy, gated compound on North Shaan Xi Road, the villa was built at the turn of the last century, and like many of Shanghai’s illustrious garden villas, it fell into disrepair following the Second Sino-Japanese war and the onset of the Cultural Revolution.

Still, the bones of the villa were intact and much of the period detailing – including plasterwork, wooden paneling, stained glass and decorative tile – was salvageable, and Mr. Baciocchi says he jumped at the chance to work on the historic building.

As relics of the city’s former international concessions, Shanghai’s villas each have their own distinctive character, a hybrid of Western sensibilities, and a unique flair and craftsmanship that are distinctly Chinese.

Rong Zhai was originally built for a German expatriate who returned to Germany following the end of WWI. The property’s subsequent owner, local business magnate Yung Tsoong-King, then had the villa remodeled. Throughout the 1920s the Beaux Arts façade was reinforced with concrete, and the rich eclectic designs of the interior were extended to historicist revival styles and modern Art Deco embellishments.

Under Mr. Baciocchi’s direction, Prada’s restoration aimed to maintain these layered, stylistic influences. The villa, which opened to the public last October as Prada Rong Zhai, will serve as a site for exhibitions, performances, and Prada’s cultural activities in China – and to this end Mr. Baciocchi left the vast interior proportions largely unchanged, focusing instead on repairing the original detailing, from inlaid chinoiserie to ceramic tiling and gilded ceilings.

Prada is known for investing in architecturally significant spaces. Since 1995, Ms. Miuccia Prada and her husband Mr. Patrizio Bertelli have been running the Milan-based Fondazione Prada as a way to bridge the worlds of fashion and art, and architecture has played a central role in this mission. “Architecture represents a way through which Prada expresses its identity,” says Mr. Stefano Cantino, Prada’s Strategic Marketing Director.

Over the years Prada has enlisted architects like Rem Koolhas and Herzog & De Meuron to design flagship stores in New York, Tokyo and Los Angeles. And the company also has extensive experience with historic preservation projects, including Milan’s 19th-century luxury shopping arcade Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II and Palazzo Ca’ Corner della Regina on the Grand Canal in Venice. With Prada Rong Zhai, the company aims to continue this tradition.

“The restoration of Rong Zhai combines that experience in historic building,” Ms. Prada says, adding that her team was careful not to exaggerate the period details. “We were especially adamant about preserving the house’s subtleties, avoiding gilded pretension.”

Mr. Baciocchi, who is known for his restrained architectural style and the crisp, monochrome interiors he has designed for Prada and Miu Miu stores around the world, seemed a natural choice for the project. He was also well acquainted with the city. “I have been familiar with Shanghai for many years and I have practically watched it grow,” he says.

The architect started by assembling a team of selected a team of around 20 Italian and Chinese artisans to undertake the conservation of the building’s many ornamental and structural elements. First, the team addressed the structural reinforcements and catalogued the villa’s original features and period details. Then, slowly and meticulously, the restoration began.

In the dining room, Mr. Baciocchi copied the profile of existing fragments to recreate missing portions of the ceiling cornice, creating a vintage effect with a lime surface coating. Then he concealed modern wiring and ventilation within the elaborate cornice, updating the space functionally without compromising its historic appearance.

In the meeting room the focal point was an original ceramic tile fireplace, which is framed by a hand-carved sculptural ornament made from solid teak. To restore the incised pattern, workers painstakingly removed a coat of paint and repaired the missing sections with wood treated to match the color of the antique surface.

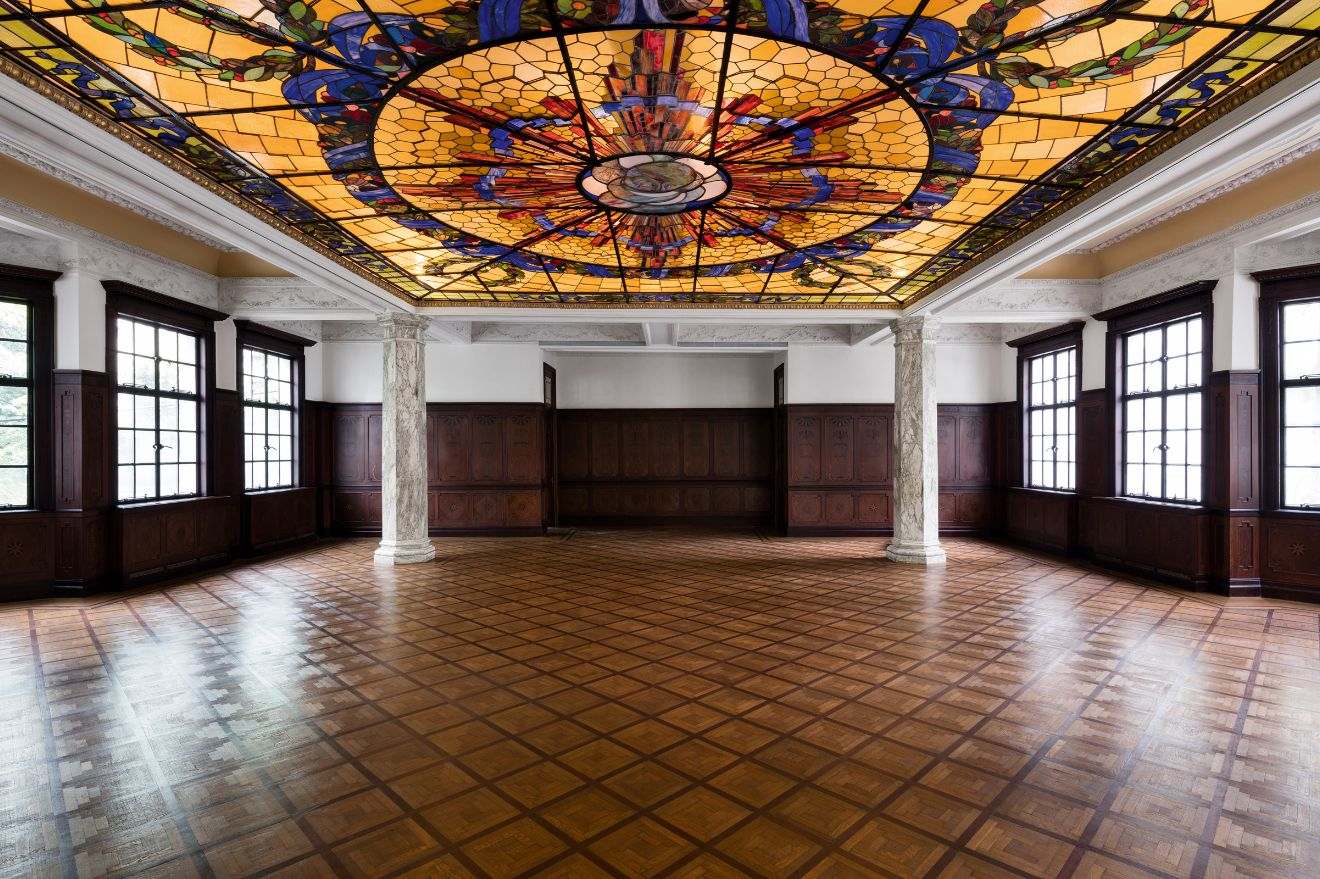

In the ballroom, the massive 45-square meter stained glass skylight had to be completely removed. The team replaced broken and missing pieces with vintage glass, and reinforced the metal support structure. And so the renovation continued, room by room.

“The objective was to bring out the quality of the original artifact,” Mr. Baciocchi says. “The ability of the craftsmen and designers to interpret an international style with personality, granting free rein to the extraordinary cultural heritage possessed only by China.”

Whenever possible the workers modeled their techniques on the traditional methods used by the craftsmen who originally built Rong Zhai. This was important not only to maintain the delicate nuance of the original materials, but because the blend of European and Chinese influences gives villas like Rong Zhai their idiosyncratic character.

The property may have been designed in Western style, but the atmosphere created by diffused light and shadow of the interior, for example, is typical to China. “Similar buildings constructed in Europe are sometimes more rigorous, and often the materials used do not contribute to ‘soften’ the spaces,” Mr. Baciocchi says.

But while the restoration aimed to delicately emulate the original, the effort at invisibility still brings attention to the many layers of interpretation and appropriation involved in the creative (and the restorative) process. When it came to the chinoiserie-style detailing found in the meeting room and other areas of the villa, for example, the craftsmen were faced with the rather bizarre task of restoring Western imitations of Chinese motifs that had been imported back to China via a Western-style villa.

But then, fashion and architecture have always been layered, interpretive acts. What ties it all together, Mr. Baciocchi says, is a scrupulous insistence on quality. “Fashion and architecture are visible expressions of a constantly evolving lifestyle,” he says. “The methodology applied for the project was in perfect tune with the Prada style, with its focus on quality and attention to detail.”

Today the villa stands juxtaposed against the gleaming modern towers of Jing-an Temple – the latest in Shanghai’s layered palimpsest of architectures – and it remains equally imposing.

Back

Back